On a Saturday afternoon in my 16th year of life, I am sprawled out on my bed with a book on the periodic table of elements. I am absorbed by the table’s symmetry (and asymmetry), how minor variations in atomic structure make the difference between gas, liquid, and solid. I pause to ponder why I’m choosing to spend my time this way, when my friends were in a nearby park tossing frisbees and smoking weed. “Because this is weird … and interesting,” I say to myself, and return to my book.

◊

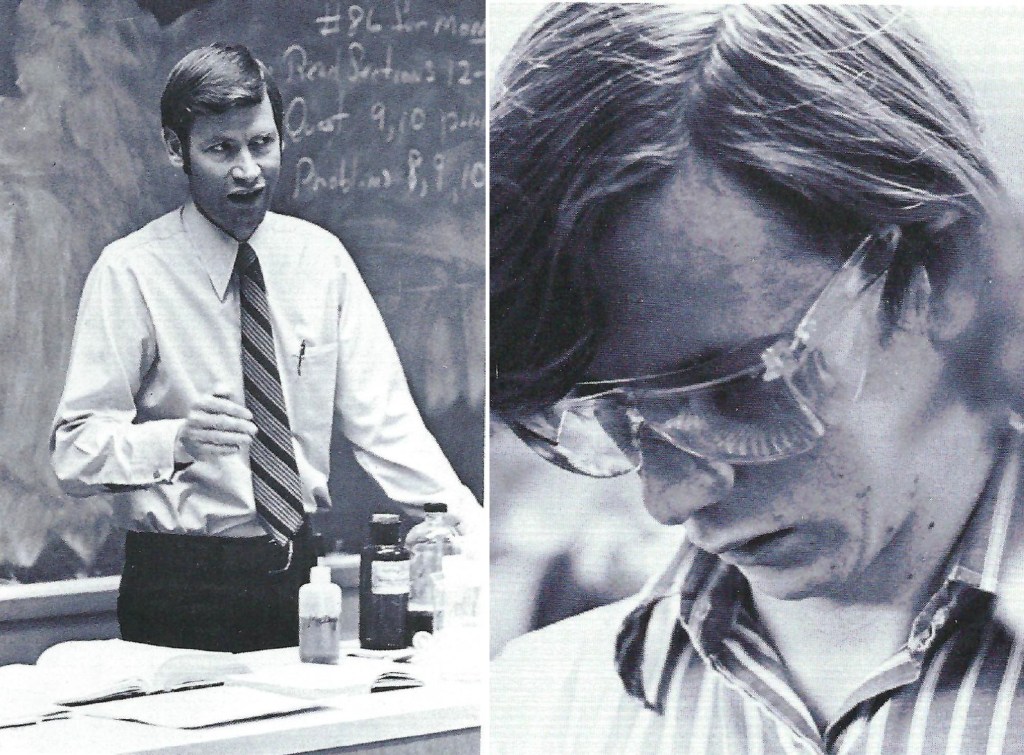

I credit this aberrant (for me) behavior to my chemistry teacher, Fred White, who died this month at 92. New to my school at that time, he was kind, quirky, and fun, and he made his subject so interesting I didn’t want class to end … so I kept at it on my own time. He explained in simple terms why carbonated beverages exude gas when shaken (H2CO3 + energy = H2O + CO2) and excited me with edgy (dangerous?) experiments like the beating heart and generating phosphine, which ignites spontaneously upon exposure to oxygen. The more I learned the more I wanted to know … a hallmark of a great teacher.

Since entering middle school my goal had been to do just well enough to stay off everyone’s radar, but my fascination with chemistry was creating a problem. I came into class one day to find my name on the corner of the blackboard, along two others at the top of my grade. I asked Mr. White why my name was up there and he said, “recruiters from MIT are visiting, and they would like to meet with you.” I asked, “Why me?” and he replied, “You might not have noticed, but you got an 800 on your chemistry SAT.” He challenged me then and there to start thinking about myself differently.

I was far from the only student wanting to keep taking classes from Mr. White. This being the early 1970s, he created a class on environmental science, introducing us to pivotal books like Silent Spring, which helped birth the environmental movement, and The Population Bomb—the latter serving as my first exposure in school to the topic of birth control. He didn’t feed us these ideas as doctrine—he encouraged our full engagement but also challenged us to assess them critically. Only now can I fully appreciate the subversive genius of this aw-shucks Midwesterner.

When my thoughts turned to college, Mr. White encouraged me to consider Reed, in Portland, OR. Just before coming to my school, he’d received a grant from the National Science Foundation to obtain a Master’s degree from Oregon State University, which brought him into contact with students and faculty at Reed. He said, “Boy, they are really bright—it seems like the kind of place you might fit in well.” Helped, no doubt, by his letter of recommendation, I was admitted, and it is now my alma mater.

His caring went beyond the classroom. A year after I graduated, I was home for a summer job, and I received a call from Fred (no longer Mr. White) out of the blue. He said, “I’ve got a really neat new sailboat—I thought you and some of the others might enjoy taking it out with me.” It was an afternoon I’ll never forget, not just for the good times shared but for reinforcing my still-fragile sense that I was a person a non-parental adult might care about, just for who I was.

Fred and I corresponded periodically as adults. Upon the occasion of his retirement I wrote a letter to Fred telling him how much he had meant to me. He responded with characteristic humility and humor. “Such a satisfaction to know that one’s efforts were worthwhile in helping you toward a bright future … Those first few years at PHS covered the spectrum from agony to ecstasy … all awkwardness and broken glass. We poisoned ourselves with regularity and relish. My moderate liquor bill became more significant! But we did have a good time and learned some good science.”

In 2001 I sent Fred a copy of Uncle Tungsten: Memories of a Chemical Childhood, by Oliver Sacks, and he responded quickly. Beyond their shared passion for chemistry, Fred noted that he and Sacks were both born in 1933 and shared many memories of a boyhood growing up in the shadows of World War II—including collecting cans and newspapers for the war effort—albeit from opposite sides of the Atlantic. Our correspondence opened up for me a whole new dimension of this marvelous and complex man.

◊

Now Mr. White is gone, joining the pantheon of those who shaped my life and now are but memories. As a chaplain and friend, I often try to comfort those grieving loss by offering wishes that the memories of their loved one provide them with solace. There is a traditional Jewish saying—”May their memory be a blessing to you”—that captures this succinctly. Even better is sharing memories with others grieving the same loss. It’s why my favorite memorial services are filled with stories of the one who has departed. I have shared these memories with friends from those days who were similarly blessed by Mr. White, and I have listened to their stories in return, we have all been blessed in the process.

I think I can best sum up Mr. White’s impact on my life with a story … In 2000 I joined several community leaders to co-found a nonprofit called Oregon Mentors (now the Institute for Youth Success), dedicated to helping youth from all walks of life find supportive adults to help guide them toward adulthood. During fundraising meetings or luncheons, we would ask those in our audience to think about a non-parental adult who’d made a big impact on who they are today. We could count on the fact that, if they’d made it into one of those rooms, they almost certainly had such a person, and this immediately connected them to our mission.

Mr. White was always that person for me. Who is it for you? I’d love to hear your stories!