As I made rounds one weekend morning, checking in at each nursing station to see if there were patients that might welcome a visit, Renee—a nurse I’d never worked with before—paused to consider my offer.

“You might want to check on the patient in 720. She’s having a really hard time. I’m not sure if she’ll be open to a chaplain visit, but she could really use some encouragement.”

I added her to my list, finished my rounds, and returned to our office to review patient charts. Ruth, in her early 40s, had no known address and no contacts. She’d been admitted for an intestinal blockage, but it was quickly determined that she also smoked fentanyl daily. She’d had surgery to address the blockage, but managing her post-op pain was proving tricky, as she was undergoing opiate withdrawal while simultaneously needing pain relief.

Ruth was asleep the first two times I came by, and Renee had urged me not to disturb her, but on my third try Renee was just leaving her room and gave me the thumbs-up. I entered the dimly lit room.

“Hi, Ruth, I’m Chaplain Greg. I’m making rounds, offering company to any who might want it. Your nurse Renee suggested I drop in to see if that’s something you’d like.”

“OK,” Ruth said listlessly, “she’s a really nice nurse.” Summoning a bit more energy, she made eye contact and asked, “How is your day going? Did you have a good Thanksgiving?”

“Thank you for asking, I did!” I responded, returning her energy.

“I’m glad to hear that,” she replied sincerely, then paused. “I didn’t really have a Thanksgiving,” she went on in a matter-of-fact way, without self-pity.

“I know life’s been hard for you recently, and now you’re in here with problems that are no fun at all.”

“No, it’s been awful, but I’m doing better now.” After silence, she continued. “My mom died suddenly two years ago. She was my best friend, and it hurt so bad to lose her. That’s when I started using fentanyl, which was stupid. It’s ruined everything.”

“Sometimes we do things to fix a problem that end up just causing bigger problems.”

“That’s the truth. But they’re telling me they can help me start getting clean.” I nod, more silence. “I have two girls in their teens, they live with their dad now, it’s been a long time since I’ve seen them. I need to get clean before they should have any reason to want to see me. I just hope they can forgive me. I want to be in their lives again, to be for them what my mom was for me.”

“Trust can be a hard thing to rebuild … they may want to see if you can stay clean over time.”

“I know it will take a long time, and I have a lot of things to figure out to set things right. But you know what they say, you have to start sometime, so why not now? That’s what I’m trying to do.”

“I admire your heart and your attitude so much,” I responded, and I offered my hand. Ruth took it, and we held hands in silence for a bit, sharing hopeful energy and prayer.

As I left I saw Renee at the nursing station, and she asked how it went.

“She’s a lovely person with a big hill to climb,” I said. “I tried to offer her what encouragement I could. She said she’d like more chaplain visits, that this was helpful.”

“I’m so glad. Sometimes a person just needs a lift at the right time, it can make all the difference.”

“But this fentanyl shit, I just hate it,” I went on. “It ruins lives, and the recovery is so long and so fraught with relapse.”

“I know … I lost my brother to fentanyl this time last year. Holidays are the hardest time of the year for so many.” Her eyes brimming, we shared a tender side hug, but couldn’t let it linger. We both had to move on—there were other patients needing our care.

◊

I have no advanced training or expertise in addiction or substance use disorders, nor in how to treat them at the individual level or address them as a matter of public health. But in my work as a chaplain I have watched the scourge of fentanyl explode in front of my eyes. I have seen the pain it has inflicted on so many patients and families I have cared for, and I just can’t let it pass without comment.

The affliction is wide. The numbers one sees in the news are abstract, but what I see through the lens of a chaplain is not. One day, when 15 of our ICU beds were occupied, three of them held men in their 30s who had OD’ed on fentanyl and were now on ventilators, fighting for their lives; I had the grim task of escorting the mothers of two of them from the waiting room to their bedside, and listen to them weep as they said, “A mother should never have to see her son like this.” Two other beds held the brain-dead bodies of fentanyl overdose victims, awaiting the harvest of their organs for transplant. That’s one third of our ICU beds—5 of 15—occupied by the victims of this scourge. I wish I could say this was an extraordinary day, but it wasn’t.

The affliction is great. I was called to the Emergency Department to help with Sandy, a patient in her 20s experiencing a fentanyl-fueled psychotic episode that had pushed the ED nurses, social worker, and security guards to the brink. For 40 minutes I held her hand, worked with her on deep breathing, and tried to calm paranoid hallucinations that made it impossible for anyone to care for her, until she bolted back out onto the streets where she was living. While other mental illness was likely involved, the sheer terror I felt in her eyes and in her grip seared my heart.

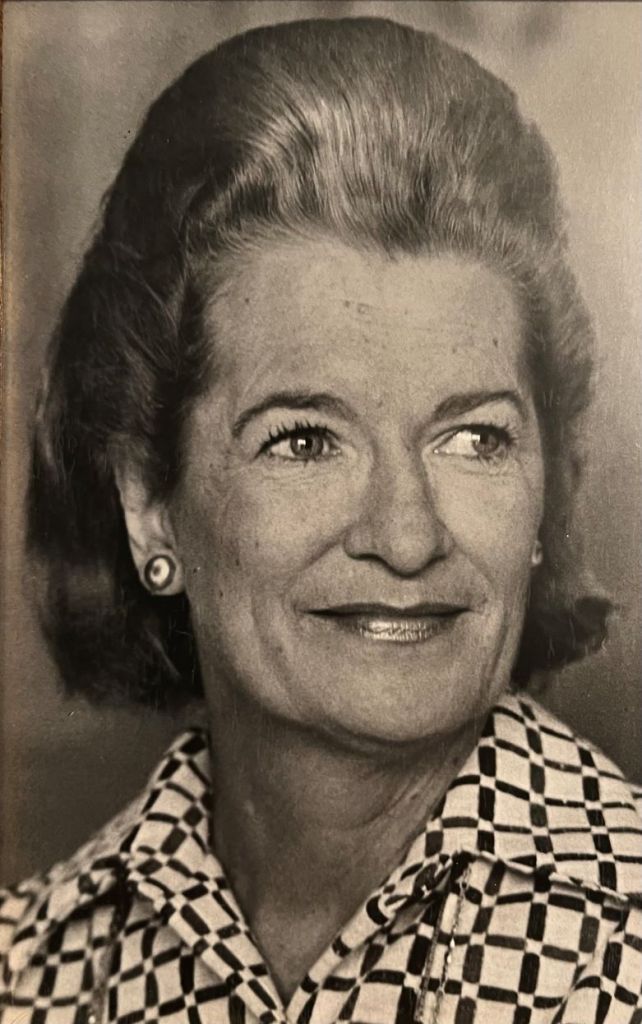

Then there is Ruth, who is a composite of patients with similar stories that I have sat with this past year. Bodies and brains damaged, families destroyed, parents lost to children, children lost to parents. Some from backgrounds with evidence of trauma, others not. Often there is a precipitating event that could happen to anyone, like the death of someone close, that starts a downward spiral, but when fentanyl is involved the descent seems especially precipitous and the ability to pull out especially difficult.

The toll of fentanyl on caregivers is also steep. It’s not just patients like Sandy, though some shifts there can be multiple patients like her in the ED, some of whom don’t survive. It’s not just patients like Ruth on the nursing floors, who, while their stories are sad, are at least trying; it’s also the ones whose bodies are so ravaged that they won’t survive another dose, yet they refuse all offers of treatment. And it’s nurses like Renee, where the scourge of fentanyl isn’t confined to the hospital, but has claimed family members or friends.

Really, it’s all of us—this scourge respects no bounds of geography or class. Some who read this have already experienced it; others may soon. As I said, I’m not qualified to propose solutions, and I have none. I only offer this: Ruth is a beautiful soul who, before being hospitalized, lived under an overpass, but before fentanyl was a devoted mother to her daughters. Sandy is a beautiful soul trapped in addiction, struggling for release. The patients in the ICU—dead and alive—have families who love them and grieve for them. I keep at this chaplaincy work in the hope that, by receiving kindness and encouragement, the goodness inside Ruth and Sandy might return to the forefront of their lives, and that loved ones might feel comfort. I tell their stories in the hope of deepening our understanding that this crisis is everyone’s problem.

Video: The Faces of Fentanyl

So this holiday season, as you see people on the street you suspect may be struggling with addiction, or as you spend time with those engaged in caring for them, my hope is that you follow the dictum of Henry James, popularized by Fred Rodgers: “Three things in human life are important. The first is to be kind. The second is to be kind. And the third is to be kind.” And think about what you might be able to do to help.

Sending love and wishes for peace and healing to all …